Helping patients with advanced mesothelioma, lung and breast cancer breathe easier

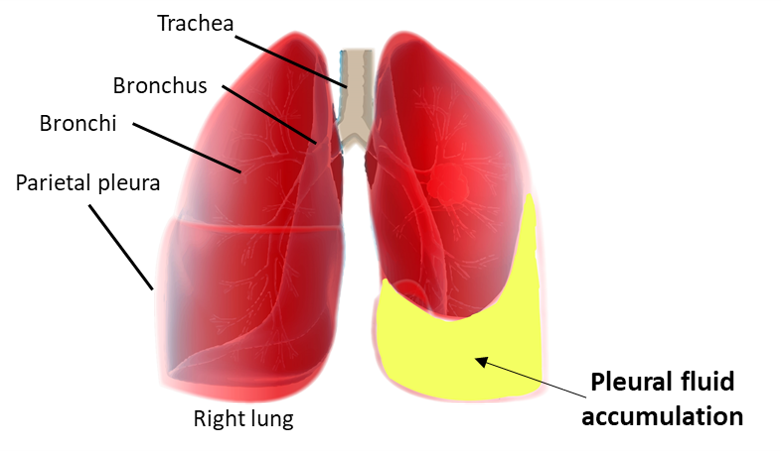

More than 8000 Australians and one million cancer patients worldwide suffer from breathlessness because of a build-up of fluid in the chest called malignant pleural effusion (MPE).

MPE can complicate most cancers, causing significant illness and death, including 1 in 4 lung and breast cancer patients. Australia has the world’s highest incidence of mesothelioma; 90% of the patients develop an MPE.

Indwelling Pleural Catheters (IPC) are small, flexible drainage tubes that allow people with a build-up of fluid compressing the lungs to drain the fluid and improve their breathing from home. This means they need fewer procedures and less time in hospital. IPC has been proven to be safe and beneficial to patients, giving them more control over their breathlessness. The next step was to improve IPC effectiveness in determining the best frequency of drainage.

The world is divided when it comes to IPC drainage management. The practice in North America is aggressive daily fluid removal via the IPC. This theoretically allows the best symptom control and maximizes physical activities. It may promote pleural symphysis – adherence of the two pleural surfaces (also termed spontaneous pleurodesis) which stops further fluid build-up meaning the catheter can be removed, thus reducing long-term costs and complications.

British centres however, believe that MPE care should be palliative and symptom-based. Fluid drainage is performed only when breathlessness occurs, typically weekly to fortnightly according to individual needs. They argue that fluid drainage in the absence of breathlessness is unlikely to improve quality of life.

The Australasian Malignant PLeural Effusion trial (AMPLE-2) addressed this clinical question the results of which will have major implications for patient care and healthcare economics worldwide.

Published in the prestigious respiratory medical journal, Lancet Respiratory Medicine, the AMPLE-2 trial compared the two standard drainage regimens (every day vs. when the patient feels breathless) using IPCs in patients with MPE.

Dr Sanjeevan Muruganandan, Dr Maree Azzopardi and Prof Gary Lee, from UWA’s Centre for Respiratory Health and School of Medicine have led this international, multicentre, randomised trial which included hospitals in Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

The AMPLE-2 study has shown that the drainage regimen holds an important key to successful use of IPCs. This study has provided an indication of the pros and cons relating to aggressive (daily) and symptom-guided drainage which will assist clinicians in the choice of regimen for their patients.

“The study found that for MPE patients treated with an IPC both drainage approaches provided similar breathlessness control. There were no significant differences in pain, days in hospital, serious adverse events or death. Daily drainage was associated with higher rates of catheter removal and better quality of life” said Dr Muruganandan.

In patients where early catheter removal is an important goal, daily drainage should be used. Alternately, for patients whose main care aim is palliation, our data showed that symptom-guided drainage offers an effective means of breathlessness control without the inconveniences and costs of daily drainages.

Future studies will need to establish if a more aggressive approach, e.g. twice daily, regimen for the initial phase, or employing aggressive drainage in combination with instilling a sclerosant agent (e.g. talc) via the IPC to create a pleurodesis, may further enhance the success rate and support earlier catheter removal.